At times, the cycling patent news cycle feels intense and a little relentless. A patent for exciting new components or some cool tech could be the next big thing; conversely, it could lead nowhere. Digging into the patent, understanding and interpreting its complex legal jargon and crafting a story can be tough and may only paint part of the picture.

Reporting on patents is one thing, but we set out to dig deeper, to dive into the world of cycling patents to learn about what they are, how they work and how brands use them to operate and develop their products.

Cyclingnews spoke with experts from around the bike world to learn more. Unsurprisingly, we found the rabbit hole goes deep.

We also spoke with Mark Aldred, a Senior Associate at Gill Jennings & Every LLP, an Intellectual Property firm in the UK. From the bike industry, we talked to Phil Nemeth, Engineering Manager, and Jay Schip, Sports Marketing and Events Manager, both at Chris King. From SRAM, we spoke with Global Director of Advanced Development, Kevin Wesling, and we also got the insight of Manuel Walker, CEO of NonPlus Components whose hubs were used to win double Olympic MTB titles this summer.

Defining a patent

It’s nice to start with a definition, and before becoming snarled up in the dense undergrowth of the patent world, let us establish what they are. Who better to ask for a definition than a patent attorney?

“A patent is a piece of intellectual property. It’s a piece of property that can be sold, assigned and utilized. So it’s an intangible thing, but it’s a piece of property that protects an invention.

“It gives the patent owner the right to control the use of that invention,” Aldred explained. “‘I’ve got a patent for invention X, what does that allow me to do’? It allows me to control the use of that invention. I could stop you from using it, or I could license it to another company, or I could sell it, I could do all sorts of things with that invention.”

Aldred also explained the relationship between the patent attorney and the client.

“My job is writing the patents. The patent that describes that new 20-speed derailleur, will have been written by someone like me.

“I work with the inventors, they describe how it works, then I would help them write the patent, my job is to represent the company in front of the patent office, who then grants the patent… hopefully! My job is the initial transfer of the inventor’s description into the legalese that you see and the patent itself.”

Why patent an invention?

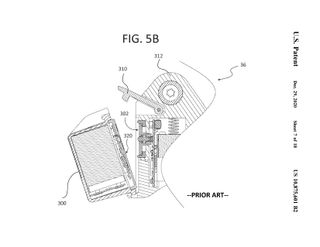

Patenting an invention helps to protect intellectual property and, at times, prevents rivals from using a company’s technology or product. A cycling-specific example here would be SRAM’s patent for an ‘electronic derailleur powered by an integrated battery’. This refers to the now-familiar SRAM eTap AXS derailleur with a removable battery. Existing patents and the need to work around them directly influenced the design of the eTap groupset, as inventor Kevin Wesling explains.

“Patents are good for the riders because they drive innovation. When we were developing eTap, we had to avoid something like 250 of our competitors’ patents. At one point, we approached one of these competitors about licensing some of their patents.

“We flew out and met with them face to face and explained why it would be a good idea. This company refused our request on the spot but as we left, they said not to worry and that SRAM would think of something new, as we had done with DoubleTap a few years earlier. It was an unexpected compliment that I appreciate to this day. And it forced us to develop eTap in a completely new direction.”

This fascinating insight confirms that patents do indeed shape the components many riders use daily and which have been raced at the top level. SRAM had to find a solution to bring eTap to market due to many existing patents and the inability to license a competitor’s existing tech.

Sign up to the Musette – our subscriber-only newsletter

Wesling also provided information on another patent that SRAM is giving away to try to make life easier for all, after developing and patenting the UDH (universal derailleur hanger), which has been widely embraced by many brands. If you have ever hunted high and low for a specific mech hanger you may empathise with this point.

“We developed UDH to simplify the bike, for bike companies and Transmission (SRAM groupset equipment). In the case of UDH, we filed patents with the sole purpose of giving those patents away and encouraging the market to adopt this as a standard. Will it stick? Will it jump to road? Who knows. But I am glad to live in a future where millions of hours are not spent looking for replacement hangers, and rather spent in better pursuits.”

The what if

What happens if a company or individual creates something which infringes a rival’s patent? There is an accepted legal process to follow, which Wesling outlined:

“If a company or a person believes that their patent is being infringed, that company is responsible for bringing an action against or to the infringer. That action can involve a letter, a conversation, or other possibilities including a lawsuit.”

However, before it comes to that, parties might agree on a licensing agreement.

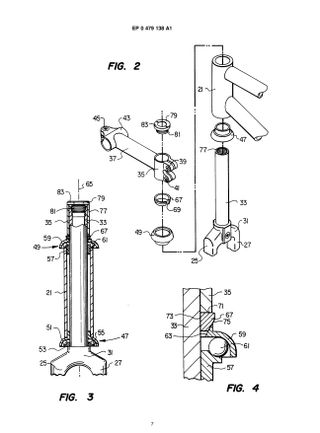

Chris King is renowned for well-engineered hubs and headsets in particular but paid a licence fee to another brand early on in its history while developing some of the first threadless (modern) headsets.

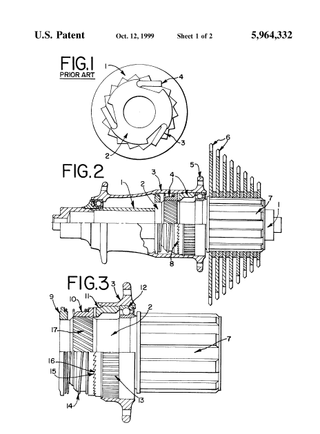

The brand takes a considered approach when it comes to patents and holds just a few specific ones of its own. The Chris King Grip Lock headset bearing cap of today is now patented, whilst the Ring Drive hub patent which protected the tech found in Chris King hubs expired in around 2019.

Chris King’s Sports Marketing and Events Manager, Jay Schip, explained the need to license some tech to get the brand’s headsets off the ground.

“We have paid royalties for someone else’s technology, Dia-Compe used to own the threadless headset patent, but Chris King was the first person who prototyped that headset. So for 20 years, Chris paid royalties to what’s called the Rader patent and paid royalties to Dia Compe.

“Eventually, Cane Creek bought Dia-Compe so he paid royalties even though he was the person to prototype the headset, and he negotiated a really low rate. Even though he never used that design in his headset production for decades, he paid royalties because his design, using his bearing cap, was part of the overall patent of John Rader and Dia-Compe.”

Patent Attorney, Aldred, explained that a patent can also be used to create additional future revenue when it creates a licensing opportunity. Hit on the right invention, patent it, agree on a licensing agreement and it could provide an additional, long-term revenue stream.

“You could license it out to another company, allow them to manufacture it and sell it, and then you get your royalties.”

On the other hand, brands may also end agreements if they can’t agree on all fronts. This is the situation German brand, NonPlus, and Tactic Racing found themselves in recently.

Tactic had purchased the NonPlus hubs for use in their Tactic hub range but ultimately the partnership came to an end in the USA.

“There was some misalignment, which ultimately led us to take the difficult decision to end the partnership,” explained NonPlus CEO, Manuel Walker.

“We currently hold four critical hub patents, which cover essential features like the toothing, hub concept, and bearing configuration in key cycling markets.”

The bike industry is relatively small and sometimes communicating a patent infringement with a partner is all that it takes. Imagine how many patents and pieces of tech there are to keep track of. Some brands will have teams dedicated to patent work.

Schip and his Chris King colleague, Phil Nemeth, explained the now-shelved Shimano Scylence hubs, or at least a part of their design, infringed on the Chris King Ring Drive patent which expired around 2019.

“They released it prior to the patent running out. We’re good partners with Shimano and Shimano is a good partner to us. We had to send a letter and say, ‘Hey, you know you guys are gonna jump the gun’. And they pulled everything. They stopped talking about it until our patent ran out.”

The project didn’t work out for Shimano long-term and the silent running hubs were cancelled, but the patent infringement point may well have influenced things.

The how

When we see a patent for what looks to be a new component, the product in question or at least the idea for it may not be particularly new at all, the idea for it will have existed for a long time.

The wait for a patent to be granted is at least 18 months and some patents may just be filed for a ‘patent pending’ label which some brands use as a marketing tool, as Aldred explained:

“You could get a ‘patent pending’ for something very quickly. You could get it today, just by filing something at the patent office, and sometimes legally that might be as far as it will go. Because the patent will never get granted.

“It’s good if you’re looking for investment, it’s good to say you have got the patent pending. It’s also good for marketing. A lot of the adverts you’ll see are for patent-pending technology or patented technology, I think that resonates with people. Even just to file a patent to say patent pending, to put on your marketing, can be quite useful.”

Aldred makes an interesting point regarding marketing and ‘patent pending’ resonating with people. Somehow this label seems to add weight when it is attached to certain pieces of marketing or products.

Walker also echoed this point regarding NonPlus’s patent activities:

“Adding ‘Patent Pending’ does serve as a strong market signal, underscoring our commitment to innovation while the design is under review.”

The where

Patents are territory-specific and when filing a patent, the companies or inventors will need to decide what territories their patent is filed in. The level of protection required will have varying costs. And it’s easy to imagine something like the latest and greatest groupset accumulating significant legal fees on its journey to market.

“Patents are territorial. If you have a UK patent, that only protects your invention in the UK. Someone could read your patent and say, ‘Oh, that’s how you do that’ and then go and do it in the US, and that third party wouldn’t be infringing your patent,” Aldred explained.

“Patent grants are territorial rights,” Wesling added, echoing the point. “They can only be enforced based on actions occurring within the jurisdiction of the patent. For example, a sale in China typically cannot be used as a basis for infringement claims in the US. To get global protection, patents need to be filed globally. Strategies on where exactly to file vary by company.”

Schip and Nemeth, however, explained that Chris King tends to only file in the US, partly because it’s difficult for people to replicate their designs well, and counterfeits are common.

Generally, if an idea or invention is deemed important enough and the holders can afford it, filing worldwide will offer the maximum protection but it won’t be cheap.

“Over the course of a worldwide patent filing program, you’re probably looking at six figures for applying and registering and keeping them in force. But you can also get a patent relatively cheaply if you only go for one country.” Aldred said.

Some of the first patents are generally acknowledged to have been granted hundreds of years ago. They provide the ability to protect intellectual property, promote the spirit of invention and help create an opportunity for legal recourse if required.

Patents are perhaps only considered when they help expose or highlight potentially exciting new technology by many of us in the bike world. Their existence has undoubtedly had an impact on and even shaped the equipment many of us ride today, promoting innovation and original thought when needed to constantly improve on what has gone before.

If you subscribe to Cyclingnews, you should sign up for our new subscriber-only newsletter. From exclusive interviews and tech galleries to race analysis and in-depth features, the Musette means you’ll never miss out on member-exclusive content. Sign up now