As I was wrapping up my review of the No.22 Great Divide, an idea struck me. Why not return it in person and check out how it was made, too?

I’m always down for a road trip, and upstate New York is a lovely area to ride, so a few emails later, plans were set and bags were packed. Here’s how No.22 Bicycles makes their gorgeous titanium road and gravel bikes and produces some of the best anodized finishes in the business…

A bit of backstory

If starting a handmade bicycle company from scratch seems like a big, complicated process, you may be surprised to know that they shipped their first bike within weeks of opening this space.

That’s partly because they started out small. There was only power line to the breaker box, which fed a few lights and outlets.

While co-founders Mike and Bryce came from the enthusiast side rather than the cycling industry, they brought several of the designers and builders from Saratoga Frameworks (formerly Serrotta). While that founding crew came from an established operation, here they had to figure out where to put things, get power to them, and create their own processes that would make No.22 unique. (Read our interview with Mike for a deeper dive on their origin story)

It started with just five people, in a smaller part of this space, and everyone was basically in the same room. They kept everything close so they didn’t have to walk all the way across the building. But as they’ve grown, things have spread out and more machines were added.

Now, they do everything in house except the 3D printing of their stem and dropouts, those are done at Silca.

Shown above are earlier machined dropouts (left), but they’ve switched to 3D printed parts (right) to get more consistent (and perfect) alignment between brake caliper mounts and the thru axle.

During COVID, they couldn’t come in and work as a team, so they used that downtime to move the heavy machinery, paint the entire interior and add more, brighter lighting. All the machines were put closer to where they needed to be, making everyone more efficient. The result is the factory you see here.

When they first started, they were ordering a couple bikes’ worth of tubing at a time, because that’s all they could afford. Which meant every tube was from a different batch, which meant they anodized differently, which was a challenge.

Now, they’re ordering six months or more worth of tubing, and making more bikes. It’s still a relatively small number – at Serrotta, they were making 12 frames a day. Here, they make four a week.

Skipping Ahead to Paint & Anodizing

While we’re on production volume, they noted that they used to produce more bikes per week, but have slowed down a little since moving all finishing in-house. Before, they would outsource it, but the quality and consistency of the work wasn’t always what they wanted.

So they brought it in-house, and now do all anodizing and Cerakote painting on site. That gives them full control, but takes longer. But that control is important because Cerakote is laid directly on the titanium with no base coat or primer, so it’ll show any imperfections in the tube, so they have to polish and finish all tubes and welds to absolute perfection first.

Media blasting booths let them give some frames (or parts of frames) a matte finish, while others (or other parts) are polished for a high gloss finish.

Cerakote comes in a wide variety of colors, and they’re all mixed and prepped on site.

They stopped doing wet paint, because Cerakote is better, lighter, more durable, and cleaner to use. It’s also immediately shippable (whereas wet paint needs to off-gas for a few days before it can be bubble wrapped…and oh boy, does No22 like their bubble wrap!).

Their paint booth is immaculate, and technically Cerakote says you don’t even need to wear a mask while spraying. They do anyway.

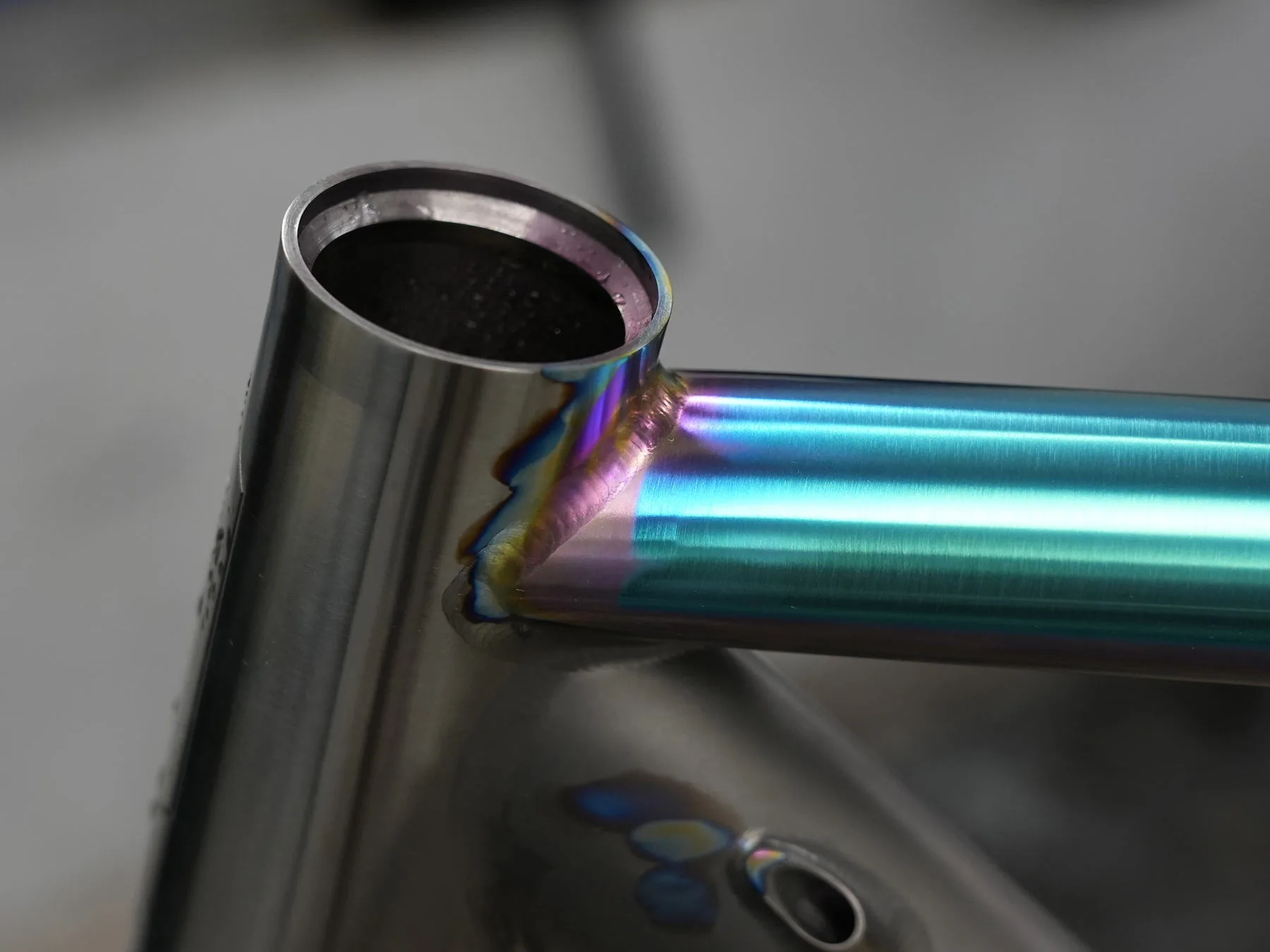

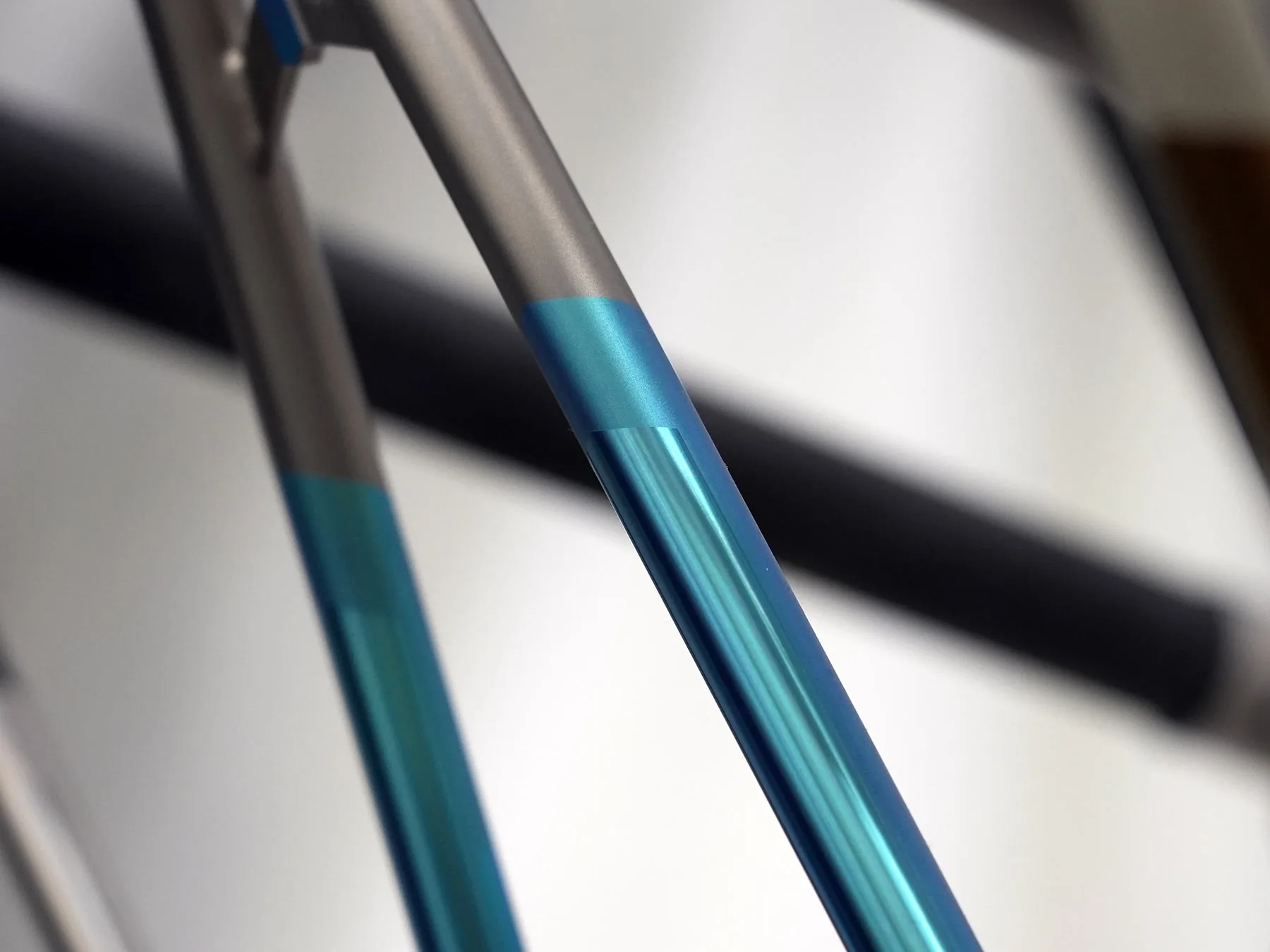

Ano is hard. The different colors are only coming from different voltage. Colors range from brass to green, created with voltage ranging from about 8 to 100 volts. Getting the fades means varying the voltage as they go, but also applying it in layers to get the higher voltage colors.

Adding to the complexity is that the color can be a little different between 6/4 and 3/2.5 titanium, and any fluctuations in the power supply can also affect the outcome. So, what you see on their frames might be 6-8 hours of anodizing on top of the prep work!

Masking, polishing, and blasting lets them get combinations of raw, gloss, and matte colors.

Vinyl decals are cut on a plotter to create the designs. They’re combined with all of the Cerakoting, anodizing, polishing, and blasting to achieve the desired outcome.

That lets them get very small details and logos across the entire frame.

How No.22 Bikes are Made

Mike or Bryce are the first point of contact. They take the order and then they or Scott do the design based on the fit numbers. Scott reviews every one, and he’s got years of experience coming from fit training and design at Serotta.

Their top tubes are mostly level, but they’ll make small tweaks to the top tube’s slope to get a seatpost logo a few mm above the collar. It’s a purely aesthetic effort, but details matter.

Customer order sheets have all the numbers, then it goes to production. They don’t do frame drawings anymore, it’s all done by number, and it’s color coded by fixture so it’s easy to efficiently run it through the system. They have machines and fixtures for most steps so that it can move through quickly without requiring a lot of extra setup steps between different tubes.

The Aurora and Reactor have a carbon seat tube and mast, and they make that with an adjustable insert rather than make the bike with a full seat tube then cut it out, saving tubing.

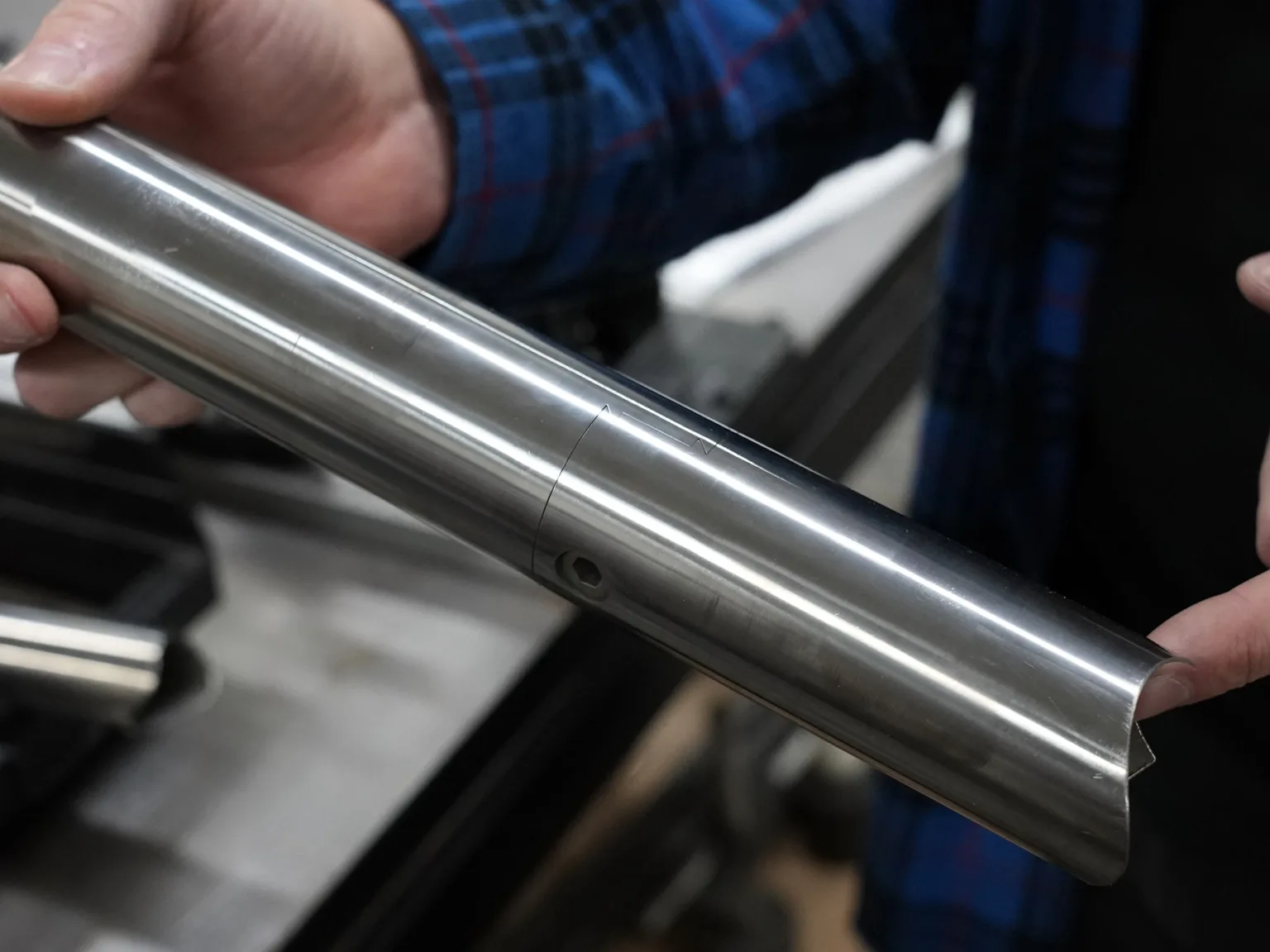

Every tube is checked for the “high side”, because they’re not straight, so they have the high side pointing straight into the inside of the front triangle, which keeps the tubes aligned. Without this, it could make the frame “lean” left or right and nearly impossible to make perfect. All that said, we’re talking about ~0.3mm variance, so it’s just a good example of the attention to detail.

Butting the main tubes saves up to 75g per tube, and also gives it a springier ride quality, and allows them to get a consistent ride quality across the size range.

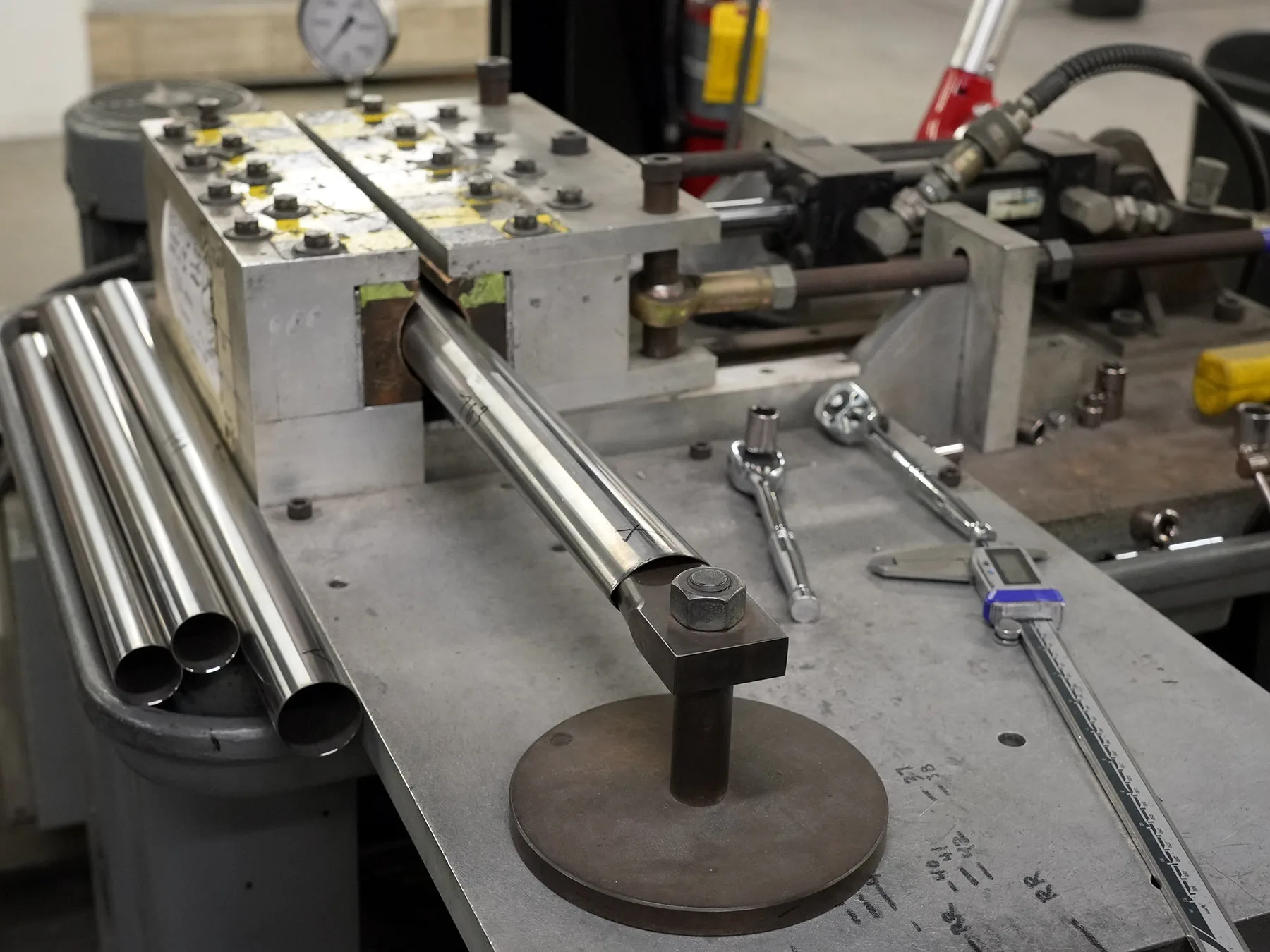

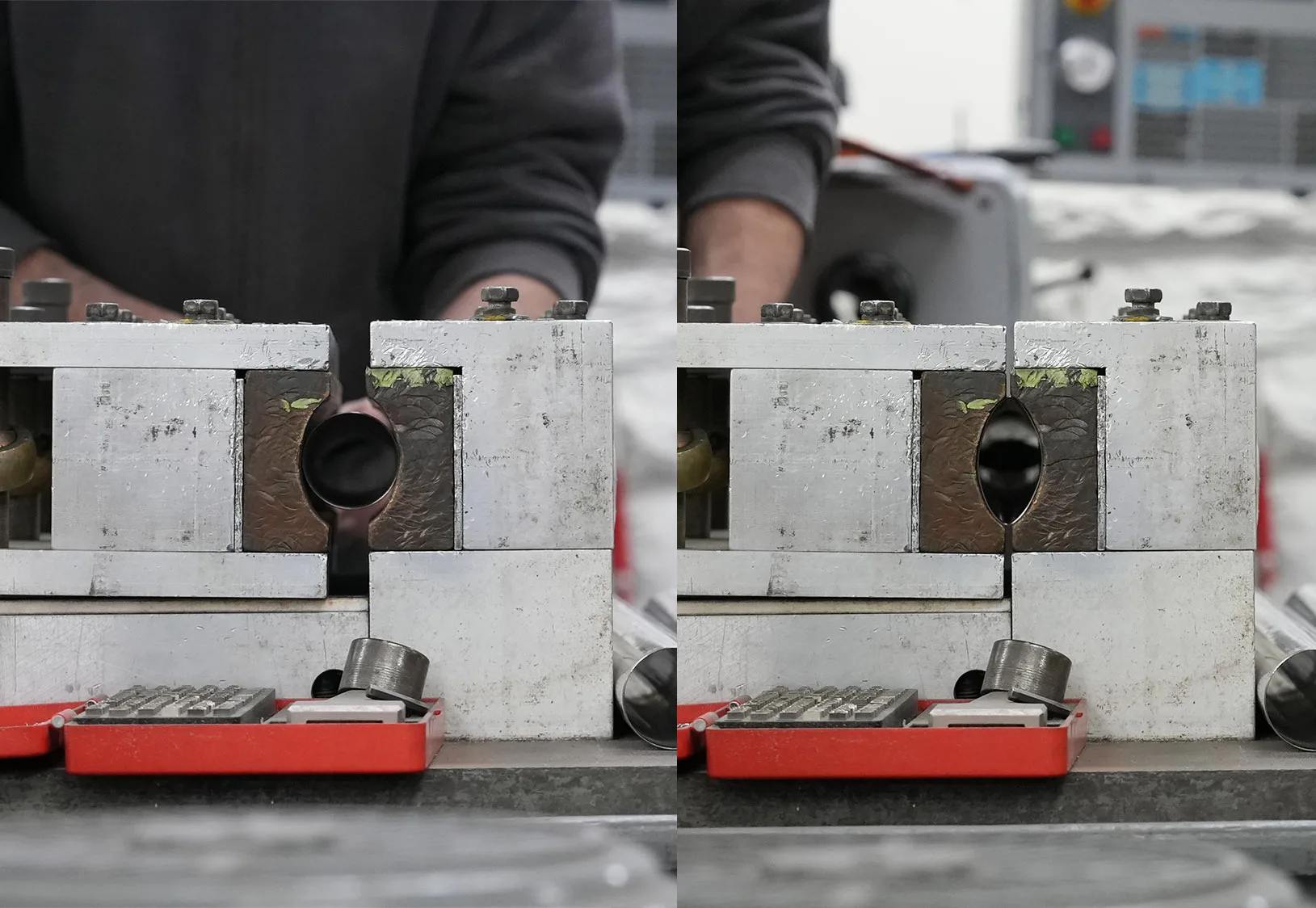

Downtubes are bi-ovalized giving them a wider stance at the bottom for a stiffer BB area, and taller at the headtube for a more streamlined appearance. The jigs above compress the tube while the other is held in place at 90º.

Serial numbers are stamped into the frame by placing individual characters into a plate, then rolling the BB shell across it under pressure. Very manual, and very cool.

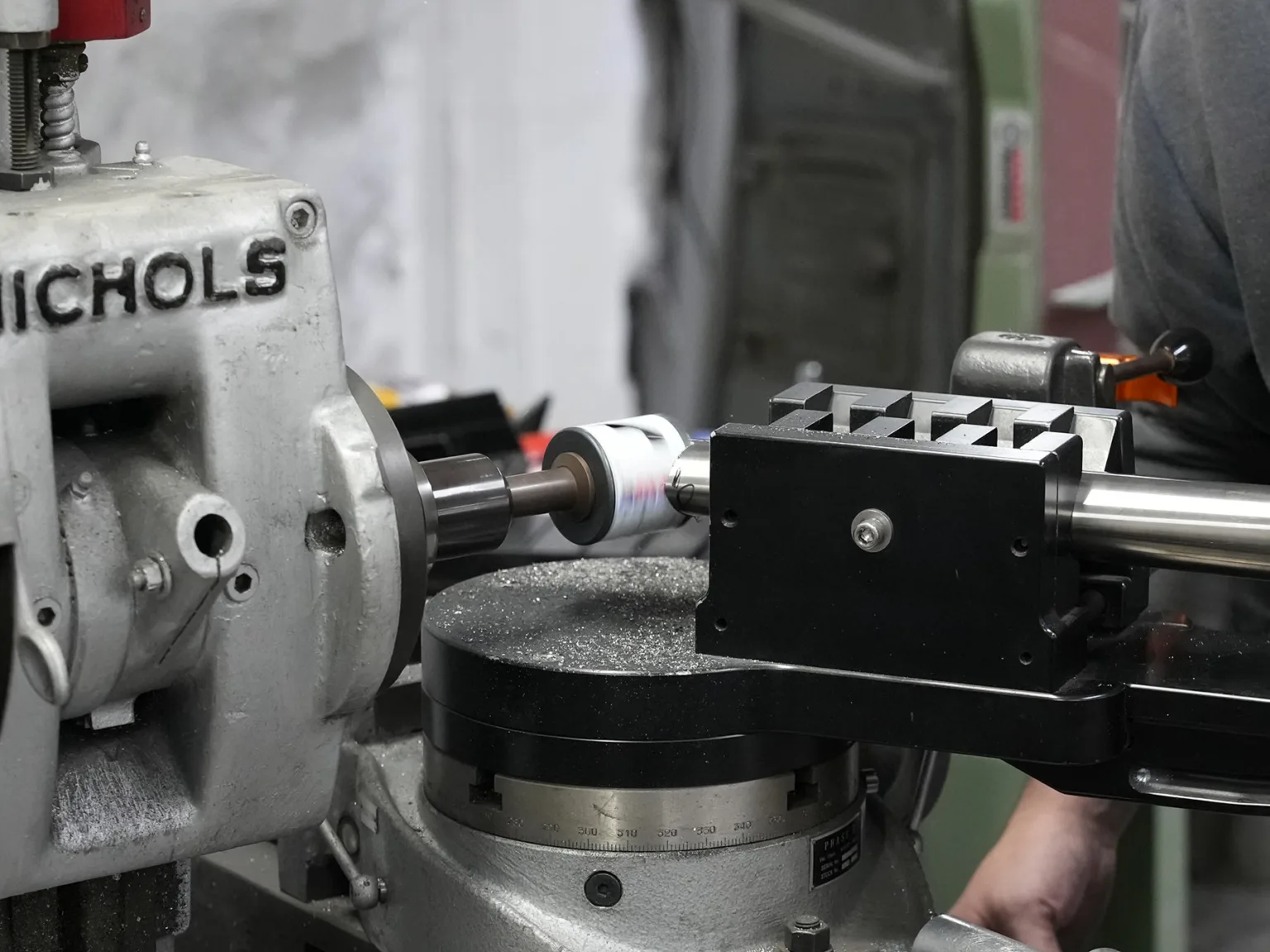

Once cut to length, tubes are mitered, drilled, and otherwise prepped for their build.

Chainstays are welded on with a wider axle spacer, because they pull inward as they’re heated, so they weld them into spec rather than having to bend them into alignment after the fact.

Main tubes are tacked, then checked for alignment between each step.

They tack in the jig, but don’t weld in it, because once it’s tacked, it’ll want to pull in one direction or another. So they’ll mark where they want to start and finish the weld so that they can literally weld it into alignment. The result is a better final product that doesn’t require manual manipulation after it’s finished.

All filing is done in a separate room so that there’s no dust, and it’s cleaned between each step. Each frame is QC’d by someone other than the welder.

After final alignment check, it gets reamed, faced, and the holes bored for cable ports, bottle cages, etc. Complete bikes are then built, and everything’s completely covered in bubble wrap and boxed up for delivery.

More Cool Stuff

No.22’s 3D-printed stems are paired with shape-matched headset spacers with ports for internal cable routing. These give the complete bike an extremely sleek, integrated look (check my review of the Great Divide for lots of photos)

While the headset cap is one piece and would require a brake line removal to change, the spacers are segmented and keyed so you can make fit adjustments…so, maybe opt for a slightly taller fork steerer if you’re not sure where you want your stack height to end up. You can always cut it down…

…but you can’t add steerer length back. The No.22 stem has a solid design, acting as top cap, too. It can be anodized to match the rest of the bike, too, as can seatmast toppers for their bikes with the carbon seat tube.

They also offer breakaway tubes with a keyed design that lets you more easily travel with your bike in a smaller case.

Huge thanks to No.22 for hosting me and showing us around the factory. Their attention to detail and pride in their work really shows through, and their finished bikes are nothing short of beautiful. They ride really nice, too! It’s nice to see a titanium brand pushing the state of the art forward, too. Their 3D-printed stems were a start, but their future Reactor aero bike takes things to another level.