Transportation politics in Vancouver, Washington got a little more interesting earlier this month when a group of grassroots activists turned in enough signatures to move their “Save our Streets” petition forward. Volunteers gathered 6,572 signatures (2,300 more than they needed) to support their goal to amend Vancouver Municipal Code to state that an election of the people must take place before the city can move forward on any project that reduces driving lanes and converts them to other uses.

“If passed, any changes to traffic lanes that result in the loss of a lane for vehicle travel will have to be approved by a majority of voters in Vancouver,” reports The Columbian.

The signatures are a huge victory for “Save Our Streets,” the group behind the petition, but they haven’t accomplished their goal just yet. In an interview with BikePortland today, Vancouver City Council Member Ty Stober explained how the initiative must still be validated by the city clerk. Whether it ultimately passes or not, Stober said the entire episode illustrates how difficult it can be to accept change.

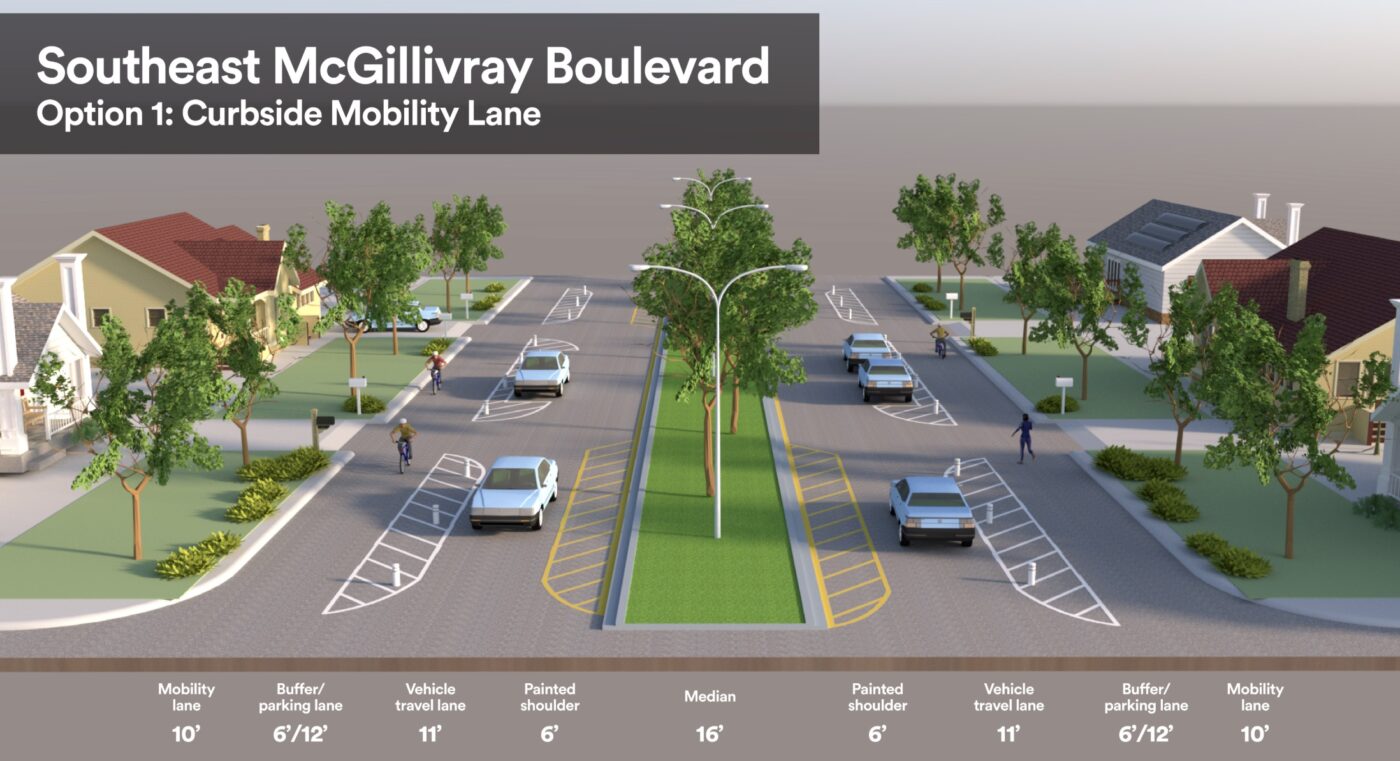

Save our Streets (the “dog” in Stober’s idiom) has pushed back on the City of Vancouver’s Complete Streets Program, which includes major road redesign projects that look to improve safety and add protected “mobility lanes” (how Vancouver smartly refers to bike lanes), reduce speeds, and improve safety. One subject of the group’s ire is a project on SE McGillivray Boulevard set to begin next year. The preferred design (above) would change the street from its current profile of six lanes for car users (four for driving, two for parking) and one narrow, unprotected bike lane; to two lanes for drivers, fewer parking spaces, and a 10-foot wide mobility lane buffered from traffic by a parking lane buffer.

That more modern, safer design is what “Save Our Streets” and their supporters want to save Vancouverites from.

One of the chief petitioners, Laurie Arndt, who’s lived a few blocks off McGillivray for 46 years, told me today she’s worried that the city’s design will lead to more dangerous driving. Not less. She says having only one lane for drivers isn’t enough. “People are very frustrated when they can’t go fast and it’s just going to cause a lot of congestion and frustration, and people will veer out of the areas that they are supposed to drive in, and they will create hazards.” Arndt also worries that when school buses let students out in the travel lane, frustrated drivers will veer into the bike lane and hit them.

The way Arndt puts it, filing the petition was a last ditch effort to get the City of Vancouver to listen to them. And she said her and her husband (who helped gather signatures with her) don’t want to take the bus and are too old to ride bikes.

Here’s the language Arndt and Save Our Streets want added to city code (and that was attached to the signature-gathering initiative form):

The City of Vancouver shall not construct or contract for the construction of any project which results in the conversion of a lane or lanes of vehicle travel on any existing principal arterial, minor arterial, collector, industrial or access street to pedestrian, bicycling, mobility, or transit use without approval by a majority of voters in the City of Vancouver in an election for the project.

This provision will apply to any applicable project approved after its enactment or to any applicable project previously approved for construction by the City in which:

1. the contract has not been awarded pursuant to a competitive bidding process or

2. funding has not been appropriated.

The Save Our Streets website offers a litany of concerns and questions about the project and states, “This is not anti bike, pedestrian or mobility lanes.” Instead of eliminating two driving lanes, they say the city should find space by narrowing the center median, and put the mobility lane on just one side of the street. Stober said he’s also aware that many Save Our Streets supporters believe increased police enforcement would accomplish the city’s goals.

The group’s main charge is a claim that changes planned for McGillivray and other streets, “are being done without community involvement.” That claim doesn’t stand up to scrutiny however, because the project spent two years in development and went through a wide range of community outreach. The City of Vancouver received 1,300 survey responses, held walk and bike audits, hosted an open house attended by 120 people (including some folks from Save Our Streets), and mailed three project flyers to over 8,000 households.

Those facts aside, Arndt says the outreach process was a sham, with city officials sharing surveys with predetermined outcomes. Ultimately, Arndt feels like the city’s plan just won’t work in her neighborhood. “Vancouver was designed as a suburb,” she said. “We understand and support busses in the city, downtown, and those kind of things. But it’s different out here in the suburbs. It just wasn’t built like that.”

Stober, a veteran of transportation project controversies now in his third term on council, is sanguine.

He chalks up the controversy to tension in the community that has built up over time. “We all want great things for our city and change is stressful,” he shared with me today. Stober also says now that the City of Vancouver’s major transportation projects are moving out of the older, more progressive-leaning, closer-in neighborhoods and into the suburbs, they are being met with stiffer opposition. He says many people who live in the Cascade Park and neighborhoods surrounding McGillivray are former Portlanders who moved to the area specifically for its suburban appeal when Interstate 205 was built in the 1980s.

“One of the messages we hear is, ‘I don’t want to live in Portland. I don’t want this to feel like Portland.’”

Vancouver City Council doesn’t want their city to feel like Portland either. Stober said they’re just trying to achieve the vision laid out in their adopted plans. “We want to create a transportation infrastructure that promotes community. We want transportation infrastructure that supports some of our more vulnerable people,” he continued. “Our elderly seniors who no longer have the ability to drive or to go outside and feel shut-in, giving our kids the opportunity to be able to play outside. We’re making decisions not just for today. We’re making decisions for generations to come.”

The next big decision the city will make will come on January 6th. That’s when the Vancouver city auditor will issue a final report on the validity of the signatures and the initiative language. If the auditor finds both are valid, the vote to enact the code changes would be in November 2025. If the initiative language is ruled to be illegal or otherwise invalid, the petitioners could sue the city. Another avenue might be a court stepping in and letting the vote happen. Then if it passes, Vancouver City Council could file suit against the petitioners to block it.

Either way, the legal process will take a while to work itself out. Meanwhile, the City of Vancouver is moving forward with the SE McGillivray project and plans to break ground this coming spring.