Metro is in the process of deciding what will be in the next iteration of its Regional Transportation Plan (RTP), the guiding document that will serve as a 25-year “blueprint to guide investments for all forms of travel” in the Portland area. The plan will include lists of priority transportation projects that are exciting to sift through and daydream about, but the people working on it also must tackle a less glamorous — and often controversial — component: how to pay for them.

A new Metro report delves into how to make sure new funding streams are fair. In the first effort of its kind, the report offers a detailed analysis of key revenue sources and rates them according to an equity score.

Metro hired a team of consultants from Nelson\Nygaard to survey the funding landscape and report back their findings. Out of this process came Metro’s Equitable Transportation Funding Research Report (PDF), which they released last month and have been discussing in meetings and work sessions since.

The research done for this report sought to benefit not only Metro planners, but also policymakers, advocacy groups, and elected officials. It tackles two main questions:

— Who does revenue collection burden and benefit the most?

— How can the revenue collection and disbursement be balanced to address inequities?

History of inequity

“The costs of car ownership comprise a sizeable portion of spending, which suggests that living in areas with less viable transportation options severely impacts financial outlooks, social mobility, jobs access, and other opportunities.”

The report begins with an overview of discriminatory planning in the Portland region. It states that events like the construction of I-5 through the historically Black Albina neighborhood “shaped the context of transportation and land use planning in the region” and that “exclusionary zoning and racial segregation still influence where people live and work today.”

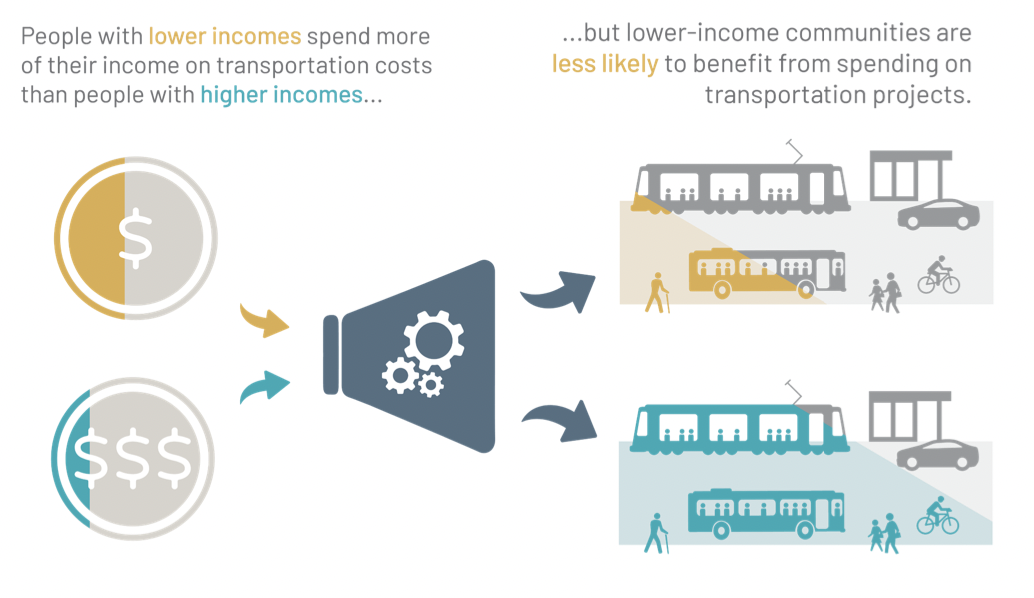

Because of this, it’s more difficult and expensive for people of color and people living on low incomes to get around the city. The report states that in the Portland region, Black commuters living below the federal poverty level have, on average, a 20% longer commute than white commuters do. They’re also more likely to live in areas on the outskirts of town where cars dominate the roads instead of the more expensive walkable, bikeable and transit-dense parts of a city, so they might feel they need to own a car even if they can’t afford to.

“The direct and recurring costs of car ownership comprise a sizeable portion of spending, which suggests that living in areas with less viable transportation options severely impacts financial outlooks, social mobility, jobs access, and other opportunities,” the report states.

Measuring current revenue streams

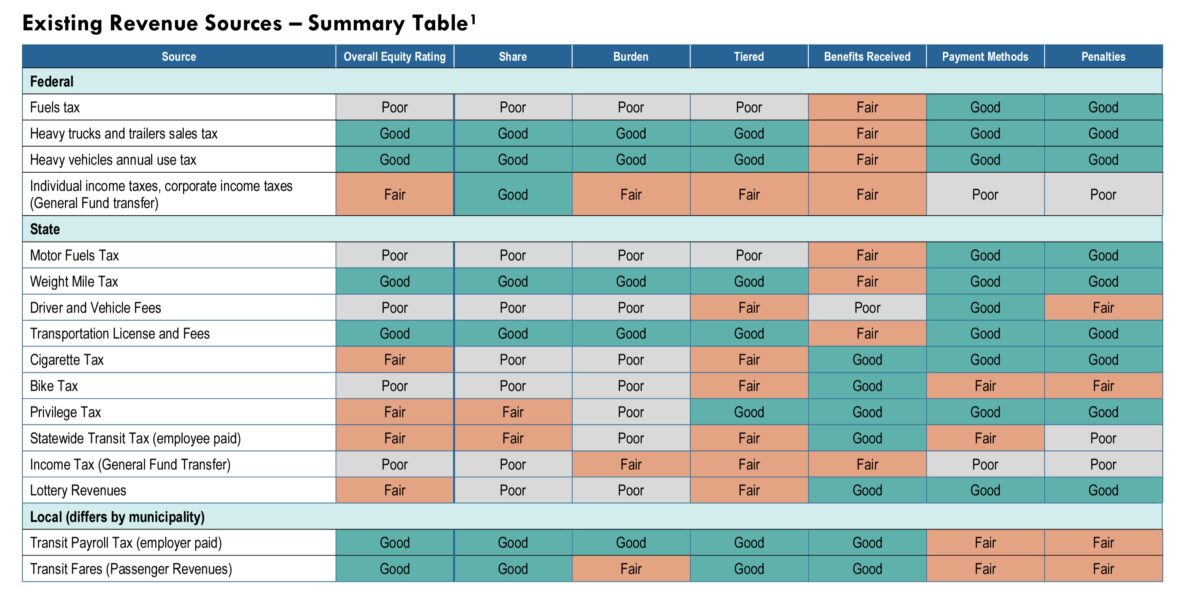

Considering all of this, the researchers came up with six equity assessment measures for revenue sources, and then gave a rating to each source. Below are the metrics they used to inform the rankings:

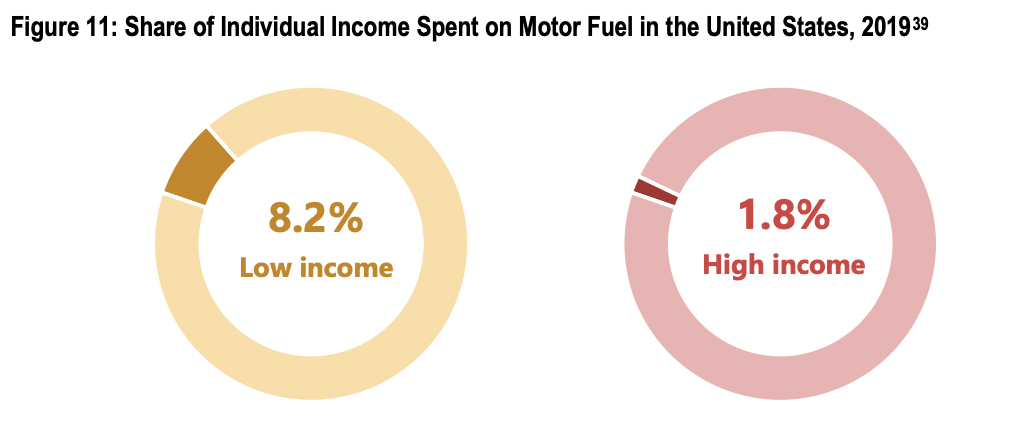

— Share: Do lower-income households pay a higher share of their income?

— Burden: Does the source provide subsidies or exemptions to alleviate unfair burdens?

— Tiered: Is the fee or tax graduated based on the value of the item?

— Benefits: Are low-income households and people of color directly benefiting?

— Payment: Are unbanked or underbanked individuals unfairly penalized?

— Penalties: Do unpaid fines, fees, or taxes trigger penalties and legal repercussions?

They used this list to analyze some current revenue streams. One of the funding sources they looked at was the gas tax, which the report says is one that has “compounding and regressive impacts on lower-income communities” because it hits harder on poorer people who are more likely to drive cars with low fuel efficiency.

The report also analyzes other income streams like transportation system development charges and property taxes, which they say are also regressive.

But there are ways to combat this. First, the report states possible revenue streams that can be applied with more discretion, like road use fees, which have “greater flexibility and potential for targeted exemptions that could mitigate outsized burden.”

Other suggestions in the report include: restructuring fines so they don’t impact credit scores or employment eligibility, prorating payments based on income, advocating for more lenient fare enforcement policies, adjusting the gas tax according to inflation, and financial assistance programs like the City of Portland’s Transportation Wallet.

Where the money goes matters

In the long-term, transportation agencies should want to use the income they receive to create a more sustainable system where people can get around without the expense of a car. This means investing in alternative transportation options in the communities that need them the most, which would mitigate some of the inequities created in revenue collection.

The report says the best way to do this is to spend money raised on projects that boost safety, transit, and biking and walking infrastructure. Other recommendations include anti-displacement strategies, and cash incentives to encourage lower-income households to reduce their carbon footprint through the purchase of things like EVs, solar panels, or transit passes.

This report is an excellent resource for anyone who wants to understand not just how transportation funding works, but how to make it work better for the people who need it most. Check out a PDF of the report here, and stay tuned for more updates on the RTP process.

Taylor has been BikePortland’s staff writer since November 2021. She has also written for Street Roots and Eugene Weekly. Contact her at taylorgriggswriter@gmail.com